Our friend, Miss Past, often tries to get our attention but we usually don’t notice her. She speaks with a sweet voice, ever so gently. On most days, though, her words barely rise above a white noise hiss. Not noticing, you and I, busy as ants on a dead beetle, fail to stand up straight from our usual getting-and-spending stoop and cock an ear to hear her. Nor do we— if we are otherwise busy—raise our heads from our leaning-forward-in-our-chair-intense-focus-on-being … uh … admit it … entertained. Entertainment is what life is about, isn’t it, our addiction? It got a big boost years ago with the telephone, then came movies, radio, and later TV, email, and the internet. Then YouTube jumped out for our attention, then Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and TikTok. Pant. Whoa! Satisfying our craving to be entertained comes right after eating, sleeping, and being safe, of course, but those fundamental needs are easily met these days by anyone reading this.

I took time yesterday to notice Miss Past’s words. Annoyed at first, I listened carefully. It was in the afternoon. She made me think about something forgotten, sad, and touching.

First, I need to help you remember what I told you earlier, namely that there are places here on Faraway Farm — I think of them as borderline enchanted, maybe slightly uncanny — where Miss Past is far easier to hear, places where she speaks so loudly her voice hits our ears like a close-by ringing bell.

One of those places is in the wooded ravine a quarter mile east of Faraway Farm house, where, at times when I am rambling around in the leaf-littered woods prospecting for wall rocks, or on the trail of wild native orchids, the distant thock-thocking of a pileated woodpecker hammers me out of my reverie. It is Miss Past’s voice, in woodpecker form, a sound that drills out the wax plugs in my ears. Hearing her, I stop, stand upright, and listen.

The other of those uncanny places is down in the park below the house to the south where the dogtrot pioneer log cabin used to stand. More about that later.

You should know that wherever Miss Past grabs my ear, she has something interesting to say.

Susie and I were down in the park yesterday. We were there because a pignut hickory tree at the edge of the woods had fallen into our cornfield. We chain-sawed it into fireplace-sized chunks and hauled it to the old shed below the house to be fed to the log splitter. We laid in a supply of firewood for next fall, stacking it in the old shed. When we finished, our thoughts turned to the new garden we had started last fall. I need to explain about that garden and how Miss Past was waiting over there.

Last fall, excited by the notion that it would be fun to expand our garden — we had somehow happened upon thoughts of growing sweet potatoes and pumpkins and gourds — Susie and I cast about for a place to put it. Those crops take up a lot of space. Our present stone-walled garden to the west of the house has no room. So where might we put a new garden? We soon hit upon a spot down in the park, a hundred yards south and downhill from the main house. It was just north of where the pioneer cabin once stood, an open space, mostly sunny through the day, and big enough. True, the area is circled by big pecan trees planted by the pioneers some 175 years ago, but they don’t give too much shade.

The alluvial soil down there is rich and black and promises a good crop. Inspired by our new garden enthusiasm, after the leaves had fallen, I attached the tiller to the John Deere and attached it to the power take-off. My plan was to till it once in the fall, leave it to settle over the winter, then till it again before we were ready to plant in the spring. In minutes It only took minutes to churn up a 50 x 50 space on the slightly sloping ground where the old log cabin had stood. Other than a couple of chunks of sandstone the tiller threw up, it left behind black, humus-rich soil that crumbled easily in my fingers.

Yesterday, on a spring-dawning day, as I said earlier, Susie and I were down at the old shed splitting wood — the old shed is an 8 x 12-foot structure built with rough sawn lumber held together with square nails (the cut type, not the hammered kind), which date it to the 1870s or before — it is the only surviving building from those early days. Oh! I should mention that there was one other reminder of the people who had once lived here: A hundred fifty feet to the southwest of the old shed is the mossy sandstone foundation of a spring house where the pioneer family kept their milk and butter cool. Gone now are the pioneer log cabin, their outhouse, and pioneer barn, all of which have long since been taken down or moldered away.

After we finished splitting firewood, Susie and I walked over to inspect the area I had plowed last fall. Thoughts of sweet potatoes and pumpkins and gourds were dancing in our heads again.

I stopped when a bit of something white and shiny in the black soil near my feet caught my eye. Bending over, I picked up a broken piece of pottery not longer than an inch and less than that wide. The rain had washed it to its purest white.

Just then I heard Miss Past’s unmistakable voice, like a bell.

She said there was a story here, and the shard reminded her of it. Would I listen? She reminded me how this shard come to be here. She said it had once been part of a plate or saucer before it was dropped by the mother of the house. She reminded me that that pioneer mother cried out as she watched it shatter irreparably on the limestone hearth, and heard the tinkling sound it made as it went to pieces. Sorry was the poor woman, the sound of it breaking hit her like needles in her heart. Glass and Chinaware, she knew, even the cheapest sort, had to be paid for with cash money, and the family had precious little of that.

Thanks to Miss Past's message, I could hear that poor woman’s cry, and then it made my imagination open its eyes and begin looking into the past. I felt a twinge of pain knowing that that precious serving China, even the cheap kind that it was, all she could barely afford, was scarce, treasured in her family, a family that was, by any modern standard, dirt poor.

Alerted by that one shard out of the past, Susie and I hunted for others, pacing back and forth across the tilled ground. We found many. Glinting in the sun was a fragment of a drinking glass. Then there was a crudely made brick, probably it had once been used in the chimney. After that, we were delighted to find two fragments of a cup that had been stained with blue markings on the rim. Such were the broken pieces of a past, each harboring untold stories.

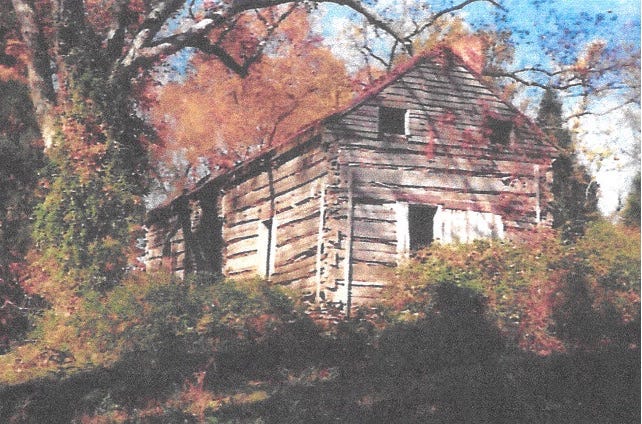

A vision of the dogtrot cabin came to my mind. We have a photo of it when it was a decaying building, the picture had been taken shortly before we bought the land on which it once stood. When the photo was taken all that remained were the logs, holes where windows once were, brick chimneys at the east and west ends, and naked rafters.

When was it built, Miss Past asked. Who built it? Where did they get the bricks? Did it have a puncheon floor or hard-packed dirt? Why did they choose to build down here in the little valley below the hill, and not higher up? The answer to the last question became clear after we had lived there for a while. It is cooler down there in the park in the summer and sheltered from the wind and the chills of winter. Not only that, there was cool spring water only a short walk from the cabin door.

Pushed to understand more of the history of the place by Miss Past, I soon learned that the land on which the cabin was built was purchased from the United States government on July 1, 1852. It became the property of Belgian immigrant Jean Baptiste Guillaume. Jean (later anglicized to John) Baptiste had immigrated to the USA on the ship Charlemagne. That canvas-sailed vessel that brought him and his family to these shores, packed with immigrants, docked in New Orleans on October 17, 1850. Millard Fillmore was President at the time when Jean Baptiste purchased the land in 1852. At the Vincennes land office, he paid $1.25/acre for the 40 acres. Jean had been born in 1814 in Chiny, Belgium, south of Brussels, and close to the border with Luxembourg. He built the dog trot cabin soon after he acquired the land and was living there in 1860 with his children, Prosper (16), Seraphina (13), Victoria (10), and Alphonsus (6). His wife Marie died July 20, 1856, probably in childbirth. The couple’s first three children were born in Belgium, the youngest in Indiana.

Jean Baptiste lived out his life in that log cabin, dying in 1898, aged 83.

What happened next? Eventually, the Guillaume land and the cabin were acquired by descendants of other Belgian immigrants, the William John Goffinet family.

Miss Past said I should pay particular attention to William U. Goffinet, born in the family cabin on December 11, 1922.

By 1940, William U.’s father William was 55 years old, and his wife Jennie was 54. In their snug little log home were three sons, Arthur, 33, Ray, 29, and our William U, 17. Two sisters, Rita, 19, and Anna, 13, made up the rest of the family. The sons helped their father with farming but got their cash income working in a nearby sawmill, each of the boys earning $8.00 per week.

The family’s dogtrot log cabin was built on a plan invented in Tennessee or Kentucky in the early pioneer days. It was practically two log cabins under a continuous roof linked by an open space several feet wide between the two units. Each of the cabin walls had glass windows, ensuring good lighting inside, necessary for a house that otherwise relied for light only on the fireplace and candles. Above each of the cabin rooms was a loft, each with small windows, the boys probably sleeping in one loft and the girls in the other. The roofed-over open space between the cabins provided good ventilation and was in summer the coolest place in the house thanks to the breeze that wafted through. The family dogs discovered this quickly as they did in all such houses, finding it a cool place to sleep in hot weather, hence the name dogtrot.

Aware of the distant drums and saber-rattling coming out of Germany and Japan, and maybe eager to see some of the big wide world, William U, 18 years old, volunteered in March 1941 to serve in the army. Educated through the 8th grade, he was six feet tall, weighed 165 lbs., and was well-muscled thanks to working in the sawmill. A promising soldier he was. He was assigned to the First Regiment of the newly formed First Armored Division at Fort Knox, Kentucky. After basic training at Fort Knox, his unit went through the Armored Force School, where the soldiers learned to drive tanks and half-tracks and fire the big guns. After additional months of training maneuvers in Louisiana, the regiment returned to Fort Knox, on December 6, 1941, the day before Pearl Harbor. After more training, the unit was shipped to Ireland the following May, traveling on a renowned ocean liner that had been pressed into military service, the Queen Mary. After a few months of additional training, the First Armored was deployed to North Africa, landing near Oran, Tunisia. There, on November 8, it became the first American armored unit to see combat in World War II. Over the next several months, the First Armored was involved in engagement after engagement in Tunisia against the formidable Afrika Korps led by General Erwin Rommel, the Desert Fox.

On March 13, 1943, William U Goffinet was declared missing in action, He must have been killed on the battlefield by the Germans. His body was never found, probably because his unit had been driven back and was forced to leave their dead behind. The family never learned how William died.

All that remains of William now is a marker in a distant cemetery in Tunisia. Perhaps a little more survives in the memories of those who knew him as a young man, a number that is surely small and slowly vanishing.

There is no record, but some weeks or months after Williams was declared missing in action, an army officer appeared at the dog trot cabin door and shared the awful news that William was missing in action and his body had not been found. The army was sure he had been killed.

The family’s only solace came from a nation grateful for the family’s sacrifice. As a consolation, they were given a gold star for their window, and a check for $10,000.

With that money, probably haunted by the ghost of their youngest son and brother, the family moved to the nearby village of Leopold, taking up residence near the town square. There they enjoyed running water for the first time in their lives, and electric lights.

Their dogtrot cabin, built nearly a hundred years earlier by immigrant Jean Baptiste Guillaume, was abandoned, never lived in again, and quickly fell into disrepair.

As for William U. Goffinet? In the North African American Cemetery, his name is inscribed on the Tablet of the Missing, in Carthage, Tunisia. Nothing else remains, except the passing memories.

Thanks, Miss Past, for the memory. I should be more alert and listen to you more than I do.

I salute you, hat in hand, William. Thanks for your service, and for giving your life fighting against authoritarian tyranny and for democracy and freedom.